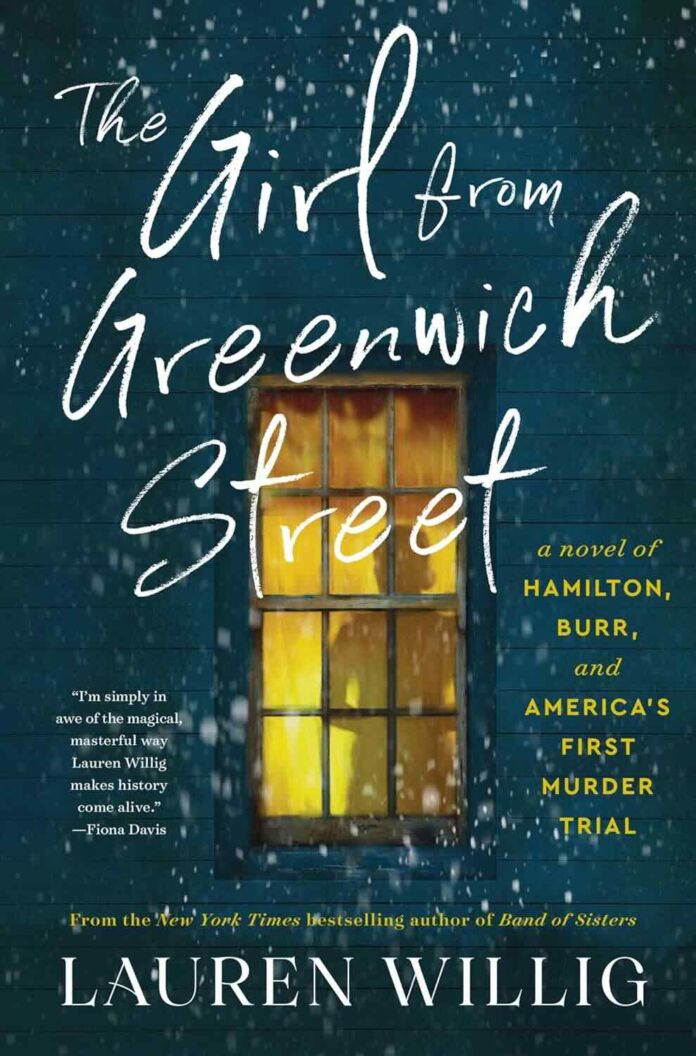

Lauren Willig masterfully resurrects one of early America’s most sensational murder trials in “The Girl from Greenwich Street,” weaving a complex tapestry of historical fact and thoughtful fiction. Set against the backdrop of a fledgling New York City in 1799-1800, this gripping narrative brilliantly explores the infamous Manhattan Well murder case—a trial that saw bitter rivals Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr join forces as defense attorneys. With meticulous attention to historical detail and remarkable psychological insight, Willig transforms dusty court transcripts into a living, breathing world of ambition, betrayal, and hidden motives.

Unlike many historical fiction novels that merely use history as wallpaper, Willig deeply embeds her narrative within the social, political, and legal frameworks of the era. The murder of Elma Sands becomes not just a mystery to be solved but a lens through which we examine the fragile foundations of American justice, the strictures facing women, and the political machinations that have always colored our pursuit of truth.

The Heart of the Mystery: Characters Who Breathe and Bleed

Willig’s greatest triumph lies in her multidimensional characterization. Rather than presenting Elma Sands as a simple victim or Levi Weeks as a clear villain, she reveals the complicated humanity behind historical figures often reduced to mere footnotes.

Elma emerges as a complex woman navigating impossible constraints—her illegitimacy marking her as an outsider even within her Quaker family. Her cousin Catherine Ring’s internal struggles between duty and resentment, between truth and family preservation, make her far more than the respectable matron history recorded. Hope Sands, whose perspective becomes increasingly central to the narrative, offers a powerful emotional anchor as she navigates her own conflicted feelings about both Elma and Levi.

Even the historical heavyweights—Hamilton, Burr, and Livingston—are rendered with nuance rather than reverence. Hamilton’s obsessive pursuit of justice battles with his equally powerful ambition; Burr’s polished charm masks calculation at every turn. These are not the marble statues of history but men of flesh and blood, driven by conflicting motives and human frailties.

A Masterclass in Historical Immersion

What separates good historical fiction from great historical fiction is the author’s ability to make readers forget they’re reading about the past. Willig accomplishes this with remarkable skill:

- Sensory details that place us firmly in 1800 New York: the stench of the glue manufactory mingling with sea air, the constant threat of yellow fever, the omnipresent mud that seeps through pattens and ruins expensive shoes

- Period-specific language that feels authentic without becoming impenetrable, particularly in her faithful reproduction of Quaker “plain speech”

- Societal structures explained naturally through character action rather than exposition

- Legal procedures of the era presented clearly, highlighting how vastly different early American jurisprudence was from our modern system

The crowning achievement is Willig’s recreation of the trial itself. Drawing directly from contemporary transcripts, she brings to life a courtroom drama that feels surprisingly modern in its strategic maneuvering while remaining firmly rooted in its time.

Thematic Richness Beyond the Whodunit

While the central mystery drives the narrative, Willig explores themes that resonate far beyond a simple murder investigation:

The Burden of Female Reputation

At every turn, women’s lives hang on the thread of their perceived virtue. Elma’s reputation becomes battleground territory during the trial, with the defense working to portray her as “melancholy” and promiscuous while the prosecution presents her as an innocent victim. Margaret Miller, Croucher’s stepdaughter and rape victim, faces similar scrutiny. As Brockholst Livingston argues in court: “When once it is known that a girl has had a connection with a man, there is instantly a strong bias in her own mind, and in those of her relations, that it should be proved to be done by violence.”

Justice vs. Political Expedience

Hamilton, Burr, and Colden all profess devotion to justice while simultaneously using the trial for political advantage. The coming election hovers over every legal maneuver, a reminder that American justice has never been isolated from political consideration.

Truth’s Many Faces

Perhaps most compelling is Willig’s exploration of how difficult truth is to discern. Each character possesses only partial knowledge, their perspectives clouded by self-interest, social pressures, and genuine belief. The reader becomes detective alongside the characters, sifting evidence that points in multiple directions.

Where the Novel Falls Short

Despite its considerable strengths, “The Girl from Greenwich Street” does have occasional weaknesses:

- The narrative sometimes feels overburdened by its commitment to historical detail, particularly during the trial scenes where the inclusion of verbatim testimony occasionally slows the pacing

- While Willig admirably juggles multiple perspectives, a few minor viewpoint characters receive less development than others

- The theoretical framework she constructs around Elma’s possible pregnancy and miscarriage, while plausible and sensitively handled, remains necessarily speculative

- The epilogue, while informative, feels somewhat disconnected from the emotional thrust of the narrative

An Author at the Height of Her Powers

Readers familiar with Willig’s previous work will recognize her signature blend of meticulous research and compelling storytelling. Like her standalone novel “The Summer Country” and her deeply affecting “Band of Sisters,” this work demonstrates her ability to craft historical fiction that educates while it entertains. However, “The Girl from Greenwich Street” ventures into darker territory than her popular Pink Carnation series, tackling themes of sexual violence, corruption, and justice denied with unflinching directness.

Fans of Stephanie Barron’s Jane Austen mysteries, Lyndsay Faye’s “The Gods of Gotham,” or E.L. Doctorow’s “The Waterworks” will find much to appreciate in Willig’s approach to historical crime and the American past.

Final Verdict: A Compelling Resurrection of a Forgotten Chapter

“The Girl from Greenwich Street” succeeds brilliantly on multiple levels:

- As a meticulously researched historical novel that brings early American legal proceedings to vivid life

- As a complex murder mystery with genuine suspense despite its basis in historical fact

- As a character study exploring the constraints on women’s lives in post-Revolutionary America

- As a political thriller capturing the bitter rivalries that would eventually lead to Hamilton’s death at Burr’s hands

For readers who appreciate historical fiction that challenges as much as it entertains, Willig’s novel offers a rich, immersive experience. It reminds us that the past is never as distant as we imagine, that human nature—in all its complicated, contradictory glory—remains a constant across centuries.

Most powerfully, it gives voice to Elma Sands herself, a woman whose death became sensation but whose life was largely forgotten. In Willig’s capable hands, she becomes not just a body in a well but a person of substance—flawed, yearning, and ultimately, deeply human. That transformation from historical footnote to fully realized character is perhaps this remarkable novel’s greatest achievement.