The Husband Stitch: Marriage, Autonomy, and Secret Selves

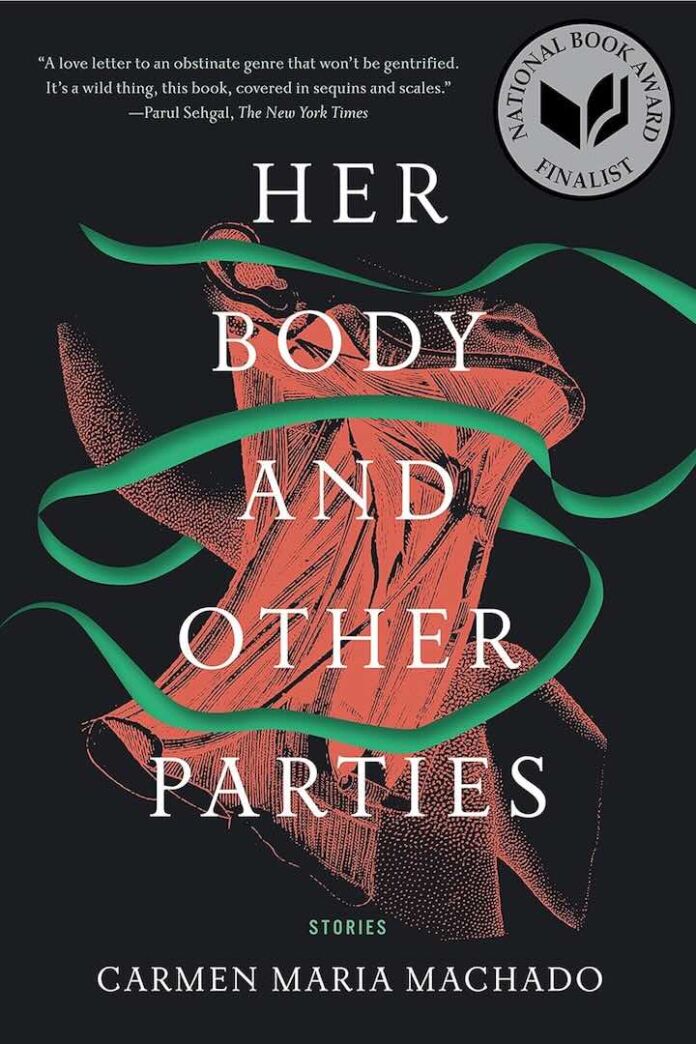

“The Husband Stitch” begins “Her Body and Other Parties” collection with Machado’s reimagining of an urban legend about a woman with a green ribbon around her neck. The story charts the progression of a relationship from youthful infatuation to marriage and motherhood, all while maintaining the central mystery of the ribbon.

What makes this tale so powerful is how Machado intertwines the supernatural element with the mundane realities of heterosexual relationships. The unnamed narrator enjoys her sexuality but gradually loses pieces of herself within marriage and motherhood. Her husband’s persistent curiosity about the ribbon—the one thing she insists on keeping private—becomes a metaphor for society’s expectation that women surrender themselves completely in relationships.

The husband’s final act of untying the ribbon (causing the narrator’s head to fall off) serves as a powerful allegory for how patriarchal systems ultimately destroy women who seek to maintain any form of autonomy. Machado enhances this tale with meta-textual elements, including instructions for different voices if read aloud, and references to other urban legends and fairy tales.

The title itself references the extra stitch sometimes given to women after childbirth to tighten the vaginal opening—a procedure explicitly performed for male pleasure rather than female healing. This medical violation of women’s bodies parallels the husband’s violation of his wife’s boundary, crystallizing the story’s feminist critique of marriage as an institution that historically consumed women’s identities.

Through lush, sensual prose and a deft blend of realism and fantasy, Machado crafts a story that feels both timeless and urgently contemporary, tracing one woman’s journey from sexual awakening to annihilation at the hands of curiosity and entitlement.

Inventory: Intimacy Against the Apocalypse

“Inventory” presents as a clinical catalog of the narrator’s sexual encounters, numbered and described with sparse detail, while in the background, a deadly plague gradually destroys civilization. This juxtaposition—between the intimacy of sexual connection and the collapse of social order—creates a haunting emotional resonance.

Each entry in the inventory reveals something about the narrator—her desires, her growth, her vulnerability—even as the world around her disintegrates. The methodical listing structure creates a false sense of control in contrast to the chaotic apocalypse. As the plague spreads, the narrator’s encounters become more desperate and meaningful, highlighting how human connection persists even in the face of extinction.

Machado’s brilliance emerges in how she conveys the apocalypse almost entirely through implication. We learn of cities quarantined, borders closed, and increasing isolation, all through casual mentions between sexual encounters. This narrative restraint makes the horror more effective—we’re experiencing the end of the world through the lens of one woman’s most intimate moments.

By the story’s conclusion, when the narrator finds herself alone on an island, potentially the last survivor, the inventory structure takes on a melancholic quality. All these connections, preserved in memory but never to be repeated, become a testament to what it means to be human. The final line—”Maybe it will go a little faster”—referring to the earth continuing to turn without humans, delivers a gut punch of existential awareness.

“Inventory” demonstrates Machado’s ability to use formal constraints to heighten emotional impact, turning a seemingly detached list into a profound meditation on intimacy, mortality, and memory during catastrophe.

Mothers: Perception, Gaslighting, and Queer Parenthood

“Mothers” from “Her Body and Other Parties” is perhaps the collection’s most disorienting tale, blurring the boundaries between reality and delusion as it explores queer parenthood, emotional abuse, and the question of whose perceptions we trust. The story centers on a relationship between the narrator and a woman called Bad, whose toxic dynamic produces—impossibly—a baby.

Machado structures the narrative to maximize reader uncertainty. As the baby appears and disappears, as memories shift and contradict themselves, we’re left questioning whether this child exists at all or is a manifestation of the narrator’s desires and traumas. This ambiguity mirrors the experience of gaslighting—being made to question your own reality—which the narrator experiences at Bad’s hands.

The story’s strength lies in its refusal to resolve this central tension. Machado depicts motherhood as simultaneously visceral and ethereal, combining detailed descriptions of infant care with surreal elements that undermine any stable reading. The scenes of domesticity imagined by the narrator—a chapel in the woods, gardens tended together, seasonal changes witnessed as a family—contrast sharply with the chaotic reality of her relationship with Bad.

Through this narrative destabilization, Machado explores how queer family structures both challenge heteronormative expectations and create unique vulnerabilities. Without socially recognized frameworks, the narrator struggles to articulate what’s happening to her and what she wants. The baby becomes both a symbol of possibility and a site of contested reality.

“Mothers” demonstrates Machado’s willingness to leave readers uncomfortable and uncertain, mirroring the confusion of abusive relationships where reality itself becomes a battleground.

Especially Heinous: Urban Hauntings and Procedural Subversion

In “Especially Heinous,” Machado undertakes her most ambitious formal experiment, reimagining 272 episodes of “Law & Order: SVU” as brief synopses that gradually construct an alternate supernatural universe. What begins as parody evolves into a phantasmagoric urban horror story featuring doppelgängers Henson and Abler, ghostly girls with bells for eyes, and a beating heart beneath Manhattan.

This novella-length piece uses the procedural format to explore how popular culture processes—and often exploits—violence against women. By introducing supernatural elements into a show already notorious for its lurid treatment of sexual violence, Machado highlights the voyeuristic nature of procedural crime dramas while creating a genuinely unsettling mythology.

The recurring motifs—girls with bells for eyes seeking justice, the mysterious heartbeat beneath the city, the uncanny doubles who seem more competent than the protagonists—create a sense of horror that deepens as the synopses progress. Machado uses the familiarity of the procedural format to lull readers before subverting expectations with increasingly bizarre and disturbing events.

What makes “Especially Heinous” remarkable is how it maintains cohesion despite its fragmented structure. The repeated characters and motifs create a hypnotic rhythm, drawing readers deeper into its nightmare logic. Benson’s gradual awareness of the supernatural elements mirrors the reader’s growing understanding of Machado’s alternate New York.

Through this experimental approach, Machado comments on how stories of violence against women are packaged for entertainment while simultaneously creating a new mythology where victims refuse to remain silent. The girls with bells for eyes represent all the women whose stories are exploited for ratings but never truly heard.

Real Women Have Bodies: Disappearance as Political Metaphor

“Real Women Have Bodies” presents a surreal scenario where women are literally fading into incorporeality, becoming transparent and eventually invisible. Set against this phenomenon, the narrator works at a dress shop where these faded women are being sewn into prom dresses, trapped in fabric to maintain their existence.

Machado crafts a powerful metaphor for how patriarchal culture simultaneously erases women while exploiting their bodies. The fading affects women of all types, suggesting that no woman—regardless of how she performs femininity—can truly thrive in a society that devalues female existence. Yet even as women disappear, they’re commodified—literally stitched into dresses to make them more appealing to consumers.

The relationship between the narrator and Petra, the delivery girl, adds emotional complexity to this political allegory. Their connection, intense but ultimately doomed as Petra begins to fade, highlights how intimacy persists even in a world that devalues women’s bodies. The sex scenes between them are rendered with tender specificity, asserting the reality of female desire in contrast to the cultural forces causing women to disappear.

What distinguishes this story from other stories in “Her Body and Other Parties” is Machado’s refusal to explain the fading phenomenon. By leaving the cause ambiguous, she forces readers to consider multiple interpretations—is it a virus, a societal curse, or a metaphysical manifestation of misogyny? This ambiguity strengthens rather than weakens the story’s impact, making it impossible to dismiss as merely fantastical.

The story’s conclusion, with the narrator cutting dresses open to free the trapped women only to discover they don’t want liberation, complicates any simple reading. Machado suggests that performing visibility within patriarchal structures might feel safer than facing the void of true disappearance, challenging readers to consider how we all participate in systems that erase women.

Eight Bites: The Horror of Self-Transformation

“Eight Bites” follows a middle-aged woman who undergoes bariatric surgery after watching her sisters transform through the same procedure. What begins as a narrative about weight loss becomes a haunting meditation on bodily autonomy, familial pressure, and the parts of ourselves we discard in pursuit of social acceptance.

The narrator’s mother’s advice—that eight bites are all you need to appreciate any food—serves as both the story’s title and its central metaphor for restriction. After surgery, the narrator begins experiencing strange phenomena, eventually discovering the discarded flesh of her former body has become a ghostly presence in her home. This apparition, formless yet undeniably present, represents everything she’s been taught to reject about herself.

Machado’s genius emerges in how she renders this supernatural element with visceral physicality. The discarded body is described in terms both monstrous and tender—a “soft, motherish thing” that follows the narrator, seeking acknowledgment. The horror comes not from the apparition itself but from the narrator’s revulsion toward her former self.

The story offers no simple moral about body positivity. Instead, it explores the complex emotions surrounding bodily transformation—the genuine pleasure the narrator takes in her new body alongside the growing awareness of what she’s lost. The final scene, where her ghostly former self carries her dying consciousness away, suggests that our discarded selves never truly disappear but remain to witness our ends.

Through precise, unflinching prose, Machado transforms what could have been a didactic tale about body image into a complex exploration of how women internalize cultural attitudes about their bodies, and the psychological consequences of attempting to excise parts of ourselves deemed unacceptable.

The Resident: Artistic Creation and Psychological Dissolution

“The Resident” is Machado’s most explicitly Gothic tale from “Her Body and Other Parties”, following a writer at an artist colony who experiences a psychological breakdown that may or may not involve supernatural elements. Set in a remote mountain location that the protagonist visited as a Girl Scout in her youth, the story explores the thin line between artistic insight and madness.

Through the protagonist’s increasingly unreliable perspective, Machado examines how women’s psychological distress is often pathologized, particularly when they refuse to conform to social expectations. The other residents’ reactions to the narrator—especially Lydia’s accusation that she’s writing a stereotypical “madwoman in the attic” narrative—highlight how female artists are often dismissed as hysterical when they explore difficult psychological terrain.

The story’s power lies in its ambiguity. Are the narrator’s visions real or hallucinated? Is the colony haunted, or is she experiencing a psychotic break? By refusing to resolve these questions, Machado suggests that the distinction may not matter—that artistic creation necessarily involves a kind of psychic destabilization that society finds threatening in women.

The Girl Scout flashback, where the protagonist was abandoned in the woods by her troop after being caught kissing another girl, provides crucial context for understanding her adult experiences. This childhood trauma, bound up with sexuality and rejection, resurfaces at the colony, suggesting that places hold memories that can reactivate past wounds.

“The Resident” culminates in the narrator’s defiant embrace of her own perspective, regardless of whether others consider it mad. By throwing her novel into the lake but adding her name to the cabin’s record, she simultaneously rejects and claims her artistic identity, embracing the destabilizing power of creation without apology.

Difficult at Parties: Trauma, Dissociation, and Recovery

The final story of “Her Body and Other Parties”, “Difficult at Parties,” centers on a woman recovering from sexual assault who develops the supernatural ability to hear the thoughts of porn performers. This uncanny power becomes a metaphor for the dissociation and hypervigilance that often accompany trauma, as the protagonist struggles to reconnect with her own sexuality while being flooded with others’ internal monologues.

Machado’s unflinching depiction of post-trauma recovery avoids both sensationalism and sentimentality. The protagonist’s relationship with Paul, her supportive but increasingly frustrated partner, illustrates how assault affects not just the survivor but those around them. Their attempts at physical intimacy, rendered with painful authenticity, show how trauma disrupts the body’s relationship to pleasure.

The supernatural element—the voices the protagonist hears beneath the performers’ scripted moans—provides a powerful metaphor for how trauma changes perception. Just as she now hears the discrepancy between the performers’ external expressions and internal thoughts, trauma has made her hyperaware of gaps between appearance and reality, leaving her constantly searching for hidden threats.

The story’s resolution avoids easy answers. The final scene, where the protagonist watches herself and Paul on video having sex after her assault, suggests a tentative step toward reclaiming her sexuality. Yet Machado resists the simple narrative that sex will “fix” trauma, instead portraying recovery as a complex, nonlinear process that involves both connection and observation of one’s own experience.

By ending “Her Body and Other Parties” with this story, Machado reminds readers that women’s bodies remain sites of violation in contemporary society, not just in the fantastical scenarios of earlier stories. “Difficult at Parties” grounds the collection’s themes in present reality while maintaining the uncanny elements that characterize Machado’s unique literary voice.