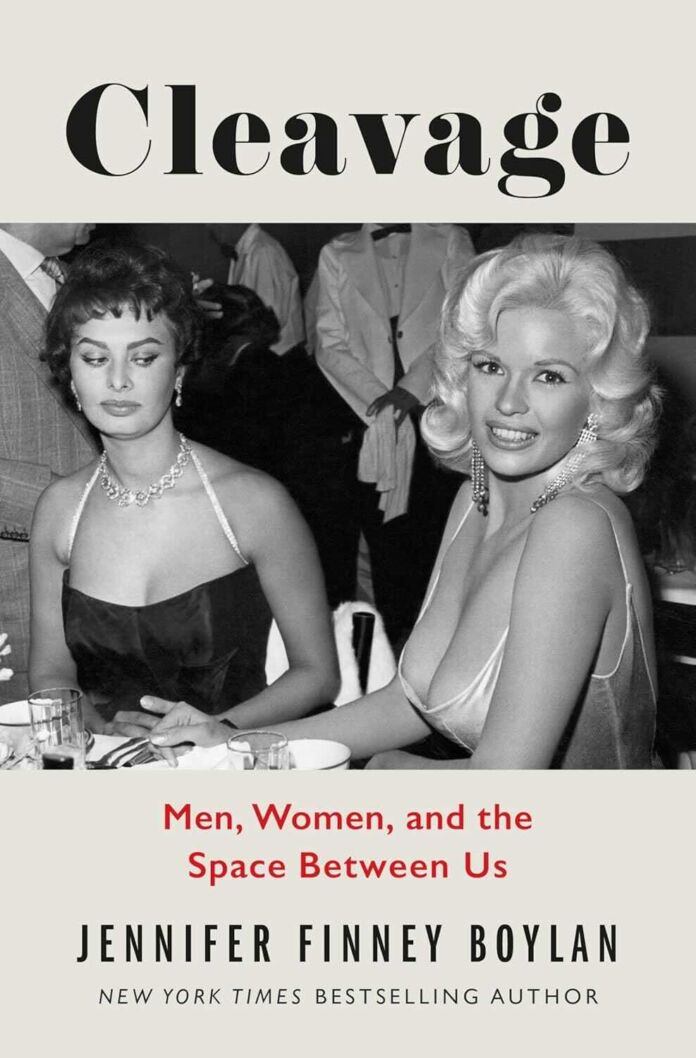

In her latest memoir, “Cleavage: Men, Women, and the Space Between Us,” Jennifer Finney Boylan offers readers a profound meditation on gender that only someone who has truly lived on both sides of the divide could provide. Twenty years after her groundbreaking memoir “She’s Not There” became the first bestseller by a transgender American, Boylan returns with a work that is both a reflection on her journey and a thoughtful examination of how gender shapes our experiences, relationships, and sense of self.

The title “Cleavage” functions brilliantly as both metaphor and organizing principle. As Boylan explains in her epilogue, the word contains its own contradiction—to cleave means both to split apart and to adhere closely. This linguistic paradox mirrors the central tension of her narrative: the ways gender divides us, while our shared humanity binds us together.

Boylan’s writing is, as always, infused with warmth, wit, and unflinching honesty. She moves effortlessly between hilarious anecdotes—like acquiring scurvy in college from a diet consisting solely of donuts and beer—to heart-wrenching moments of vulnerability, such as watching her wife Deedie sing to her in the hospital after gender-affirming surgery. Through it all, she maintains a voice that is distinctly her own: thoughtful, self-deprecating, and fundamentally kind.

The Shifting Landscape of Trans Experience

One of the most compelling aspects of “Cleavage” is Jennifer Finney Boylan’s comparison between coming out as transgender in the early 2000s versus today’s more polarized climate. She notes that when she came out to her evangelical Christian mother decades ago, the response was simple: “Love will prevail.” There were no lectures about transgender athletes or accusations of “social contagion“—just a mother embracing her child.

This observation feels particularly poignant given the current wave of anti-transgender legislation sweeping through many states. Boylan doesn’t shy away from these realities, but neither does she allow them to overwhelm her narrative. Instead, she offers her story as a counterbalance to dehumanizing political rhetoric—a reminder that behind every statistic is a human being with dreams, flaws, and an innate desire to be known.

Perhaps the most moving section of the book comes when Boylan discovers that her own child, Zach, is transgender. The revelation forces her to confront her own complicated feelings:

“Is it possible, I wondered, that I made this look like fun? Could my daughter have possibly looked at the intricacies of my life—of our lives—and not seen how hard it all had been, how there were times when I’d felt like I was clutching for dear life onto a tiny life preserver in the middle of a swirling, freezing sea?”

Her daughter Zai’s transition becomes a mirror reflecting Boylan’s own journey, but from a different generational perspective. The contrast between Boylan’s more medicalized, binary transition and her daughter’s more fluid understanding of gender highlights how quickly the conversation around gender identity has evolved.

Strengths and Shortcomings

Where “Cleavage” by Jennifer Finney Boylan truly excels is in its exploration of the minutiae of gendered experience. Boylan’s observations about how differently she was received as a professor before and after transition—from unquestioned authority figure to someone whose expertise is constantly challenged—cut to the heart of everyday sexism. Similarly, her reflections on body image, voice, and food illuminate how profoundly gender shapes our relationship with our bodies.

In her chapter on food, Boylan writes about making elaborate pizzas in a wood-fired oven, noting how differently she experiences weight gain as a woman than she did as a man:

“When I was a man (sic), I can say most definitively that it had not [mattered]. I’d had the same sense of myself as a boyo back then whether I was a slender willow tree (as I’d been throughout all my teens and twenties) or whether I was more the size of stately oak (my size in my thirties and forties).”

These insights, drawn from direct experience of both sides of the gender divide, give the book its unique power.

However, “Cleavage” occasionally suffers from a certain meandering quality. Some stories feel disconnected from the central thesis, and at times the chronology becomes confusing as Boylan jumps between different periods of her life. While this structure mimics the way memory actually works—associative rather than linear—it can occasionally leave the reader disoriented.

Additionally, readers familiar with Boylan’s previous works will find some repetition of anecdotes and themes. The rich material on her childhood, particularly her relationship with her father, treads ground covered in earlier memoirs, albeit with new insights gained through the perspective of age.

Beyond the Binary: Expanding the Conversation

What sets “Cleavage” apart from Jennifer Finney Boylan’s earlier work is her evolving perspective on gender itself. While her own journey followed a more traditional male-to-female narrative, she acknowledges and celebrates younger generations who inhabit nonbinary and genderfluid identities with a freedom that wasn’t available to her.

In a particularly insightful passage, she reflects on her daughter’s generation:

“Even now, among many good-hearted people, I hear resistance to the singular ‘they.’ Oh, I want everyone to feel accepted, they say. But it’s bad grammar! That’s what I resent!

Sometimes I suspect that what people really resent is not the change in grammar. What people resent is being told that the world that they have known has changed, and that even now they have to get used to something new.”

This gracious embrace of evolving language and concepts demonstrates Boylan’s intellectual generosity and her commitment to an expansive understanding of gender that goes beyond her own experience.

The Healing Power of Humor

Throughout “Cleavage,” Jennifer Finney Boylan deploys humor as both shield and salve. In one memorable scene, she describes attending a ventriloquists’ convention where a man in a bar keeps trying to pick her up, his dummy urging him on from a trunk. The absurdity of the situation highlights the bizarre social dynamics transgender women often navigate, while making readers laugh out loud.

This ability to find comedy in difficult circumstances is perhaps Boylan’s greatest gift as a writer. Even when describing moments of discrimination or fear, she maintains a fundamental optimism about human nature. This is not naivete but a hard-won belief in the possibility of connection across differences.

A Compassionate Guide Through Gender’s Complexities

For readers new to transgender literature, “Cleavage” by Jennifer Finney Boylan offers an accessible entry point, balancing personal narrative with thoughtful reflections on gender that never become overly academic. For those already familiar with Boylan’s work or with transgender memoirs more broadly, the book provides fresh insights on familiar themes, particularly through her experience witnessing her own child’s gender journey.

In comparing “Cleavage” to other notable transgender memoirs like Deirdre McCloskey’s “Crossing” or Thomas Page McBee’s “Amateur,” what stands out is Boylan’s unique longitudinal perspective. Having transitioned over twenty years ago, she can speak not only to the process of transition itself but to the long life that follows—with all its ordinary joys, sorrows, and complications.

Final Assessment: A Worthy Addition to the Gender Canon

“Cleavage” by Jennifer Finney Boylan is not a perfect book. It occasionally loses focus and revisits territory Boylan has covered elsewhere. But these minor flaws are easily forgiven in light of the work’s considerable strengths: its wisdom, compassion, and genuine desire to bridge divides rather than deepen them.

At its heart, this is a book about the fundamental challenge of human existence—how we can truly know and be known by others across the divides of gender, generation, and experience. Through her willingness to share her most vulnerable moments and her most hard-won insights, Boylan creates a space where readers of all genders can recognize something of themselves.

As she writes in her epilogue: “In the end, the bodies we find ourselves in may matter less than the souls that inhabit them. And during our time on earth, it is surely no sin to do what you can to find your happiness within the body you’re in.”

For readers seeking a thoughtful, humane exploration of gender from someone who has truly seen it from both sides now, “Cleavage” offers not just information but illumination. In a cultural moment when transgender lives have become politicized battlegrounds, Boylan’s gentle reminder of our shared humanity feels both necessary and healing. Like the contrasting definitions of its title, the book both divides and connects—ultimately leaving readers with a deeper understanding of not just transgender experience, but what it means to be human.