Title: The Snows of Kilimanjaro

Author: Ernest Hemingway

Genre: Short Story

First Publication: 1936

Language: English

Summary: The Snows of Kilimanjaro by Ernest Hemingway

The Snows of Kilimanjaro — written in 1938 — reflects several of Hemingway’s personal concerns during the 1930s regarding his existence as a writer and his life in general. Hemingway remarked in Green Hills that “politics, women, drink, money, and ambition” damage American writers. His fear that his own acquaintances with rich people might harm his integrity as a writer becomes evident in this story. The text in italics also reveals Hemingway’s fear of leaving his own work of life unfinished.

In broader terms, The Snows of Kilimanjaro should be viewed as an example of an author of the “Lost Generation”, who experienced the world wars and the war in Spain, which led them to question moral and philosophy. Hemingway, in particular, found himself in a moral vacuum when he felt alienated from the church, which was closely affiliated with Franco in Spain, and which he felt obliged to distance himself from. As a result, he came up with his own code of human conduct: a mixture of hedonism and sentimental humanism.

Review: The Snows of Kilimanjaro by Ernest Hemingway

The Snows of Kilimanjaro is a short story by American author Ernest Hemingway. First published in 1936, it is considered one of Hemingway’s finest works and most famous stories. The story examines themes of regret, wasted talent, life choices, death, and the complicated relationship between men and women.

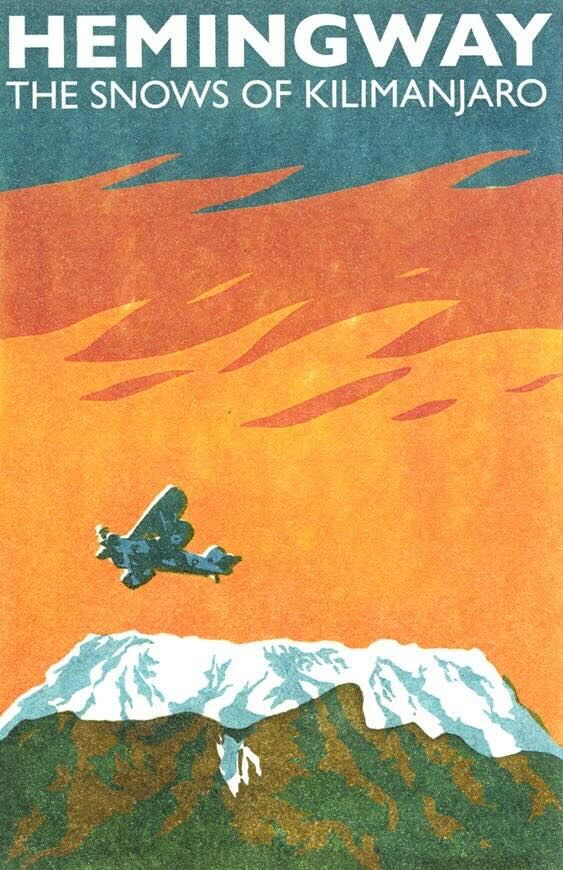

Set in the African savannah, the story centers on a dying writer named Harry and his rich wife Helen, who are stranded while on safari due to Harry’s infected leg. As Harry lies mortally ill and waits for a rescue plane, he is irritated by Helen’s optimistically making future plans, starkly contrasted with his own despair and facing of death. Through a series of flashbacks, we learn about Harry’s past, his failed marriage to another woman named Helen, and his regret about not writing all the stories he planned to write. His nostalgia for his past life of adventure and travel represents regret about choosing comfort and steady income over his creative passion.

The central irony arises from the act that, as Harry lies dying in Africa, his dream was to write stories about Africa gained from his experiences there. Key symbols, especially the snow-covered peak of Kilimanjaro, represent his unfulfilled creative aspirations and the purity of past hopes now dying with him. Harry chose safety and stability in his marriage to the wealthy Helen over the life of struggle and adventure that might have fueled his writing. He alludes to short stories he never wrote—vivid ideas that could have comprised his life’s work. Instead, he has perished in Africa without truly absorbing and conveying through writing what the continent meant to him.

Juxtaposed flashbacks convey the wasted promise of Harry’s talent. When urged to write by fellow expats, he brushes them off for comforts like drinking and sex. However, his nostalgia for the past reveals deep regrets about that squandered potential. Helen, meanwhile, represents how domesticity and marriage later led him to abandon his craft. Her optimism about his survival highlights her inability to comprehend the depth of his regrets as death approaches.

Critics have noted Hemingway himself was wary of declining into drunkenness and living off his wife rather than pursuing the rugged life that inspired his writing. Thus, Harry and his nostalgia may represent the author’s own fears of squandered talent. Harry’s bitterness about exchanging adventure for lazy comfort makes his impending death uniquely painful since it ends his chances for redemption. His failure to write the vivid stories in his memory represents a metaphor for this wasted gift.

With its modernist blend of terse dialogue, introspection, and fragmented scenes, “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” exemplifies Hemingway’s stripped-down prose style. The repetitive flashbacks of remembered conversations echo in Harry’s mind like haunting condemnation as he awaits death. The juxtaposition of the past and present builds regret and tension. In spare but evocative language, Hemingway conveys the psychology of facing death with both nostalgia for a squandered life and liberation that the end finally nears.

Harry remains an enigma – it is unclear if his stated regrets at the end are genuine or still more self-pity before his death, which comes almost as a relief. Yet his fate serves as a parable about avoiding complacency and compromise of one’s dreams, even through socially accepted means like marriage or steady income. The story continues to move readers through its contemplation of mortality, talent lost versus engaged, and the complexity of love, compromise, and regret when a life ends unfulfilled.